The jet-setting Dr. Ranjini George holds a PhD in English Literature from Northern Illinois University, an MA in English Literature from St. Stephen’s College, New Delhi, India, and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia, Canada. More recently, she won the first place in Canada’s inaugural Coffee Shop Author Contest for her travel memoir, a work-in-progress titled Miracle of Flowers: In the Footsteps of an Emperor, a Goddess, a Story and a Tiffin-Stall.

She’s been an Associate Professor of English at Zayed University, Dubai, and currently teaches Stoicism, Mindfulness and Creative Writing at the School of Continuing Studies, University of Toronto. In 2019, she received the Excellence in Teaching award. A list of her courses is here. Her book, Through My Mother’s Window: Emirati Women Tell their Stories and Recipes, was published in Dubai in December 2016. Find her at @RanjiniGeorge1 on Twitter, at TheKuanYinStoryCafe on Facebook, or on her website.

1. What first drew you to Stoicism?

In Grade Ten in New Delhi, I played Marc Anthony in a performance of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Dressed in a pinned-up table cloth and a plain six-yard sari vaguely approximating Marlon Brando’s dress in Julius Caesar, I strode the stage, a grieving and courageous Anthony, and declaimed my lines with gusto. But barring this, I knew more of Indian than Roman History.

Fast forward some decades, in Dubai, I received the gift of a Roman bust of Antoninus Pius, the adoptive father of Marcus Aurelius. At first, I didn’t know whom the bust represented. The story of discovering his name and subsequent journeys to places associated with him—such as Ancient Agora in Athens and the Antonine Wall in Scotland—are the subject of my prize-winning memoir-in-progress Miracle of Flowers: In the Footsteps of an Emperor, a Goddess, a Story and a Tiffin-Stall.

This year, I was fortunate to receive an Ontario Arts Council Recommender Grant for Writers from Cormorant Books to continue work on my memoir. It includes both a personal narrative—my immigration to Canada and the unraveling of my first marriage—as well as a philosophical narrative about my study of Stoicism and Buddhism. Both philosophies offered me a way of life and a “therapy for the soul.”

A key point in my Stoic journey came when I read Donald Robertson’s How to Think Like a Roman Emperor. Books can change one’s life and this one did.

2. You are deeply committed to Buddhism. What’s an area where you think Buddhism has better answers than Stoicism?

Stoicism reminds us of the necessity of kindness and fellowship. It speaks of the cosmopolis, an idea that brings to mind what my Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh names “inter-being.” Stoicism includes practices such as ways of dealing with anger (see for example the chapter on “Temporary Madness” and the discussion of the Ten Gifts of Apollo in How to Think Like a Roman Emperor). As Stoics, we can practice meditations such as View from Above, Stoic Mindfulness and Stoic journaling.

In Zen Buddhism wisdom is not an intellectual exercise but an embodied experience that includes mindful walking and sitting and a wide range of compassion and contemplative practices. As the Dalai Lama says, these practices can offer us a “secular ethics”—we don’t need to be a Buddhist to engage in these practices, just as you don’t have to be Chinese to eat Chinese food.

In the Zen lineage the recitation of gathas or short verses that accompany ever day actions such as brushing one’s teeth or drinking tea are helpful in reminding us of our core values and training our body, speech and mind. These gathas are offered by Thich Nhat Hanh in his book, Present Moment, Wonderful Moment: Mindfulness Verses for Daily Living .

Brushing Your Teeth

Brushing my teeth, and rinsing my mouth,

I vow to speak purely and lovingly.

When my mouth is fragrant with right speech,

a flower blooms in the garden of my heart.

Drinking Tea

This cup of tea in my two hands,

mindfulness held perfectly.

My mind and body dwell

in the very here and now.

Buddhist mindfulness is reduced in contemporary discussion to present moment awareness. It is labeled as a “tool” for stress reduction. Such an understanding is a watered-down version of what Buddhist mindfulness is—a practice that includes the three times of past, present and future. Buddhist mindfulness includes deep looking, insight and concentration. As my Zen teacher reminds us, and as poets such as William Blake and Walt Whitman write, if we look deeply at a flower, we will see the whole cosmos—sun, earth, rain, and wind.

Buddhism includes the component of retreats that range from one-day, weekend, weeklong to yearlong retreats. Buddhist retreats include dharma (wisdom) teachings, discussion and sharing, Noble Silence, sitting and walking meditation, sessions for deep guided relaxation, music and singing. Less than two weeks ago, I attended such a retreat hosted in Durham College in Oshawa, Ontario taught by the Plum Village monastics, a tradition founded by my teacher Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh.

In the Zen tradition wisdom (awakening) is not an intellectual exercise but an embodied experience of body, mind and spirit. The Buddhist practice of slowing down, sitting and walking and silence have deeply nourished me and so has my study of Stoicism.

Stoic events, insofar as we now have them now, include talks and discussion. We discuss Stoic Mindfulness, and sometimes we sit for brief moments and engage in short contemplative practices. Perhaps a greater emphasis on these or other such practices would be beneficial. After all, Stoicism is a “therapy” of the soul.

Donald Robertson points out that

The Greek word “therapeia” (θεραπεία) is derived from the Greek verb “therapeuo” (θεραπεύω), which means “to serve” or “to attend to.” The ancient Greeks believed the interconnectedness of the mind, body, and spirit, and therapy encompassed all aspects of holistic healing. Within Greek mythology, the gods themselves were often associated with therapeutic practices. For example, Apollo, the Greek god of healing, was often invoked for the restoration of physical and mental health. So, therapeia was sometimes used to describe the activities carried out in Apollo’s temples, where individuals sought healing through prayer, offerings, and ritual practices.”

We may not believe in Apollo or gods or prayers or offerings but we can include other mindfulness practices, such as Noble silence and slowing down, and loving kindness (metta) practices. Perhaps we need to find ways in the Stoicism community where the path to wisdom encompasses holistic healing as it does in Buddhist communities.

3. How does Stoicism inform the way you write?

Stoicism, like Buddhism, teaches me to write simply and clearly. Our desire is not to impress others with our intellect and by how much we know but to share what we have learned and to be of benefit. My teacher Thich Nhat Hanh distills complex philosophy and teaching in a way that is understandable. It is this quality of making complex ideas and narratives simple that particularly drew me to Donald’s How to Think like a Roman Emperor. Through powerful storytelling, grounded in research and the Meditations, Donald evokes the presence of Marcus the man—the Emperor and the Stoic. It is a difficult endeavor to combine history, psychotherapy, and philosophy, but Donald does this in a clear and memorable way.

4. How does Stoicism inform the way you teach writing?

First, let me begin with Buddhism. In Buddhism there is no hierarchy between the teacher and student. We all inter-are. As Thich Nhat Hanh writes in At Home in the World: “When I teach a friend to practice meditation, I don’t call myself ‘teacher’ and my friend ‘student.’ There is no transmitter and no receiver. We are one and the same. Together, we help each other grow.”

Though the word Buddhist comes from the Awakened One, the Buddha, Buddha nature exists in each one of us. As the Heart Sutra reminds us, the one who is bowed to and the one who bows are the same.

As Stoics, we don’t take our name from Zeno, but from the Stoa Poikile, the Painted Porch, in the ancient Agora where Stoicism was first taught. We are unlike the Epicureans who took their name from Epicurus. This presupposes a non-hierarchical community of philosophers gathering under a literal or metaphorical stoa.

Second, I encourage students to be present to the page and not fixate on outcome. Stoic mindfulness and Buddhist mindfulness with its emphasis on the work to be done in the present moment is important.

Third, in encouraging students to let go of outcome (publication) and find joy in the process of writing, I draw on Stoic wisdom. Books take a long time to write and publication is uncertain (an external, and so not up to us). How our book is received is another external: we cannot control the judgement of others. One of the hardest balances to maintain as we work hard toward a goal is this: What happens if we fail? What happens when we don’t receive praise? What happens if this work never comes to be in the world because of external factors such as one’s health and longevity? Perfectionism and procrastination can stem from fear and worry and feelings of inadequacy. Stoicism helps me continue joyfully as a writer and to simply do my work as a human being.

To give just one example from the Meditations (there are many…), in book 3, verse 12, Marcus writes:

“If you accomplish the task set before you, following right reason and with dedication, steadfastness, and good humor, and you never allow secondary issues to distract you but keep the deity within you pure and upright, as if you might have to surrender it at any moment; if you hold on to this, awaiting nothing and fleeing from nothing, but remaining satisfied if you present action is in accordance with nature…you will live a happy life; and no one can stand in your way.”

In this verse, Marcus emphasizes the principle of dispassion and engagement. When we sit at our writing desk, we are doing our work as human being. We are exercising the virtue of discipline. We are reminding ourselves to stay in the present moment, be present and to do our work well. We put aside our future hopes for this project. We do our work to the best of our ability and we do it with joy.

In Buddhism, of course, we have the same emphasis on dispassion and engagement. One of my Dalai Lama calendar quotes reads: “Peace and equanimity come from letting go of our attachment to the goal and the method. That is the essence of acceptance.” He also reminds us, “All human life is some part failure and some part achievement.” He says contemplate your intentions and motivation. Ask yourself if your goal is “noble” and generous. If it is, whether you fail or succeed is irrelevant.

Fourth, let writing be about writing. Natalie Goldberg, whose book Writing Down the Bones I use in my Meditation and Writing classes at the School of Continuing Studies, University of Toronto, reminds us that writing has to be about writing.

So, let whatever you do be about the work itself. The rest you can work towards, but its results are not up to you. Once you arrive at a decision, arrange your time, your life accordingly. Throw yourself wholeheartedly into your work, and for every failure, say what the Stoics say about “externals” over which we have no control, “It is nothing to me.” It is the good endeavor that counts: the effort and self-discipline, the joy you feel from the moment of doing and being, and the good use that you are making of your precious human life. Virtue exists in that moment when you show up and sit and work at your writing desk.

5. When was the last time you screamed your lungs out for any reason?

I’ll pass on this question!

Bonus question: What should we have asked you, and what’s the answer?

“How was the Stoic Summit 2023 on April 1st in Tampa Florida? “

This event hosted by Brittany Polat and Phil Yanov earlier this year was excellent. It was good to finally meet Phil and other Stoic friends who I’d only met in online Stoic events. Brittany is a dear friend and an inspiration—compassionate, generous, and wise. Brittany’s work on Stoicare and with the Stoicon Women’s event are important contributions to the Stoic community.

It was wonderful gathering together as a community after such a long time. The lineup of speakers and the location were both lovely.

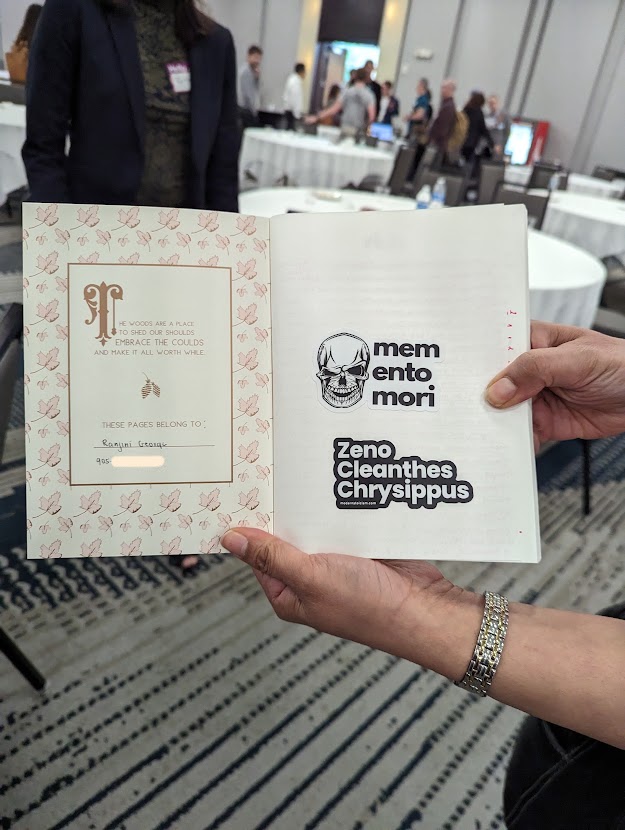

Sunday morning after the conference was a treat—an unexpected outing with new friends—the gorgeous and courageous Karen Duffy and the creative and kind Francis Gasparini! It was great visiting the wonderful Salvador Dali Museum. Dali’s work occupies not just one wing of the museum, but many floors. It is hard to imagine that all this is one human being’s extraordinary creativity and accomplishment; and, yes, the architecture of the museum is stunning. I count myself fortunate to have good friends and mentors within the Stoic community. I treasure these pictures from the weekend in Tampa–including my journal with Phil’s stickers!